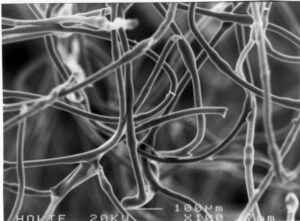

[Image credit: “Kapok fibre structure” by CORE-Materials is licensed under CC BY 2.0]

The presence of fibres on a person or object is a relatively common feature of serious criminal cases, in particular cases of murder or other serious violence.

Fibres can be easily transferred, and their presence can indicate a link between people, locations and/or objects.

We know that a significant transfer of fibres can take place from simple contact between two objects, so if two people are involved in an altercation, it is quite likely that fibres from both persons may transfer onto the other person. Accordingly, a denial by person B that he has ever met person A can, as a starting point, be easily refuted.

Forensically and legally, this is not the end of the story, and we must go on to consider issues of secondary transfer, eg transfers from A were passed to C who passed them to B. Or that the fibre transfer was as a result of the fibres being airborne, then later depositing on a person or object. In these two scenarios, the hypothesis that there has been direct contact between A and B is broken.

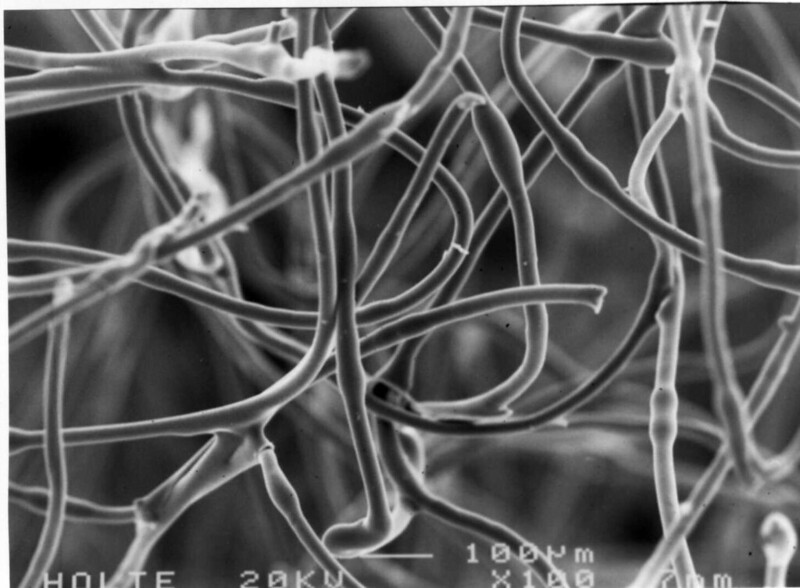

In recent research, scientists explored the contactless airborne transfer of textile fibres, but in compact semi-enclosed spaces, for example, a lift.

So, if we take this scenario:

A is murdered in a hotel room. Fibres from A are found on B, who denies all contact with A. It can be demonstrated from CCTV footage that A and B travelled together in a hotel elevator, but do not make physical contact with each other at any time. Could this suggest that the fibre transfer may have taken place in the elevator, as opposed to later during a confrontation?

The findings of the research were that:

“It was proven, not only that this transfer mechanism is fully possible in authentic forensic scenarios (both as primary and secondary transfer), but also that the number of fibres transferred could be particularly significant for certain types of textile materials (such as cotton and polyester) and, importantly, comparable to other transfer mechanisms involving contact. Therefore, the potential for contactless fibre transfer should be carefully assessed in real casework and appropriately taken into account in the interpretation of findings at activity level. In this respect, the authors believe that the empirical data provided in this work may constitute a reference point.”

Given this conclusion, we can see that there is some strength in the argument that the fibres do not necessarily demonstrate direct physical contact between A and B, thereby seriously undermining any prosecution case in this respect.

Conclusion

Increasingly, the successful defence of criminal cases depends not only on an understanding of criminal law but also of areas of forensic and other evidence. Our lawyers ensure that they are kept updated on all aspects of forensic evidence. You only have once chance to fight your case, and it should not be left to chance.

How can we help?

If you need specialist advice, then get in touch with any member of our vastly experienced Criminal Defence team, for assistance with any criminal law related matter.

–

Mr John Stokes (John.Stokes@danielwoodman.co.uk),

Mr Anthony Pearce (Anthony.Pearce@danielwoodman.co.uk) or

Mr Daniel Woodman (Daniel.Woodman@danielwoodman.co.uk).